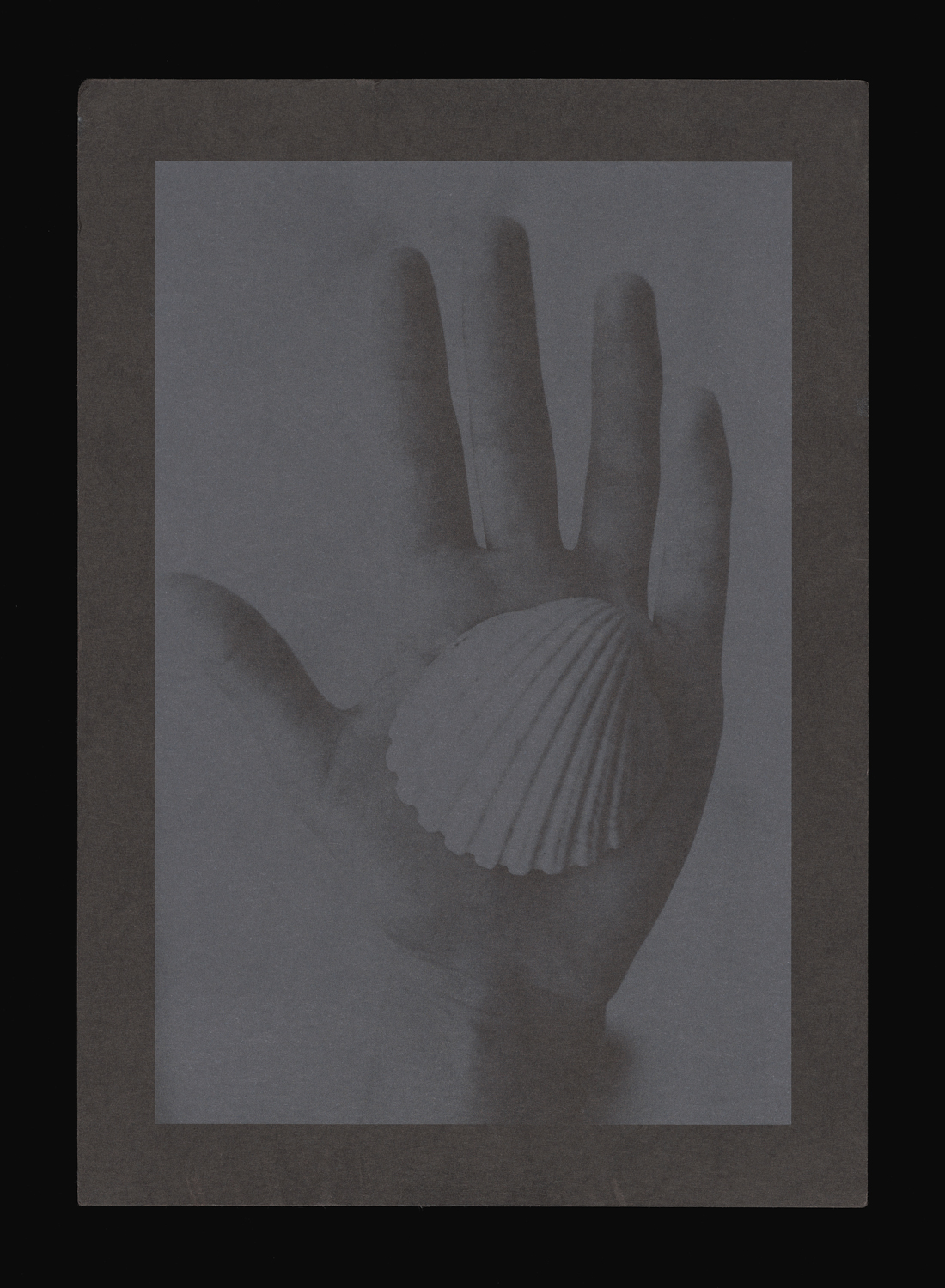

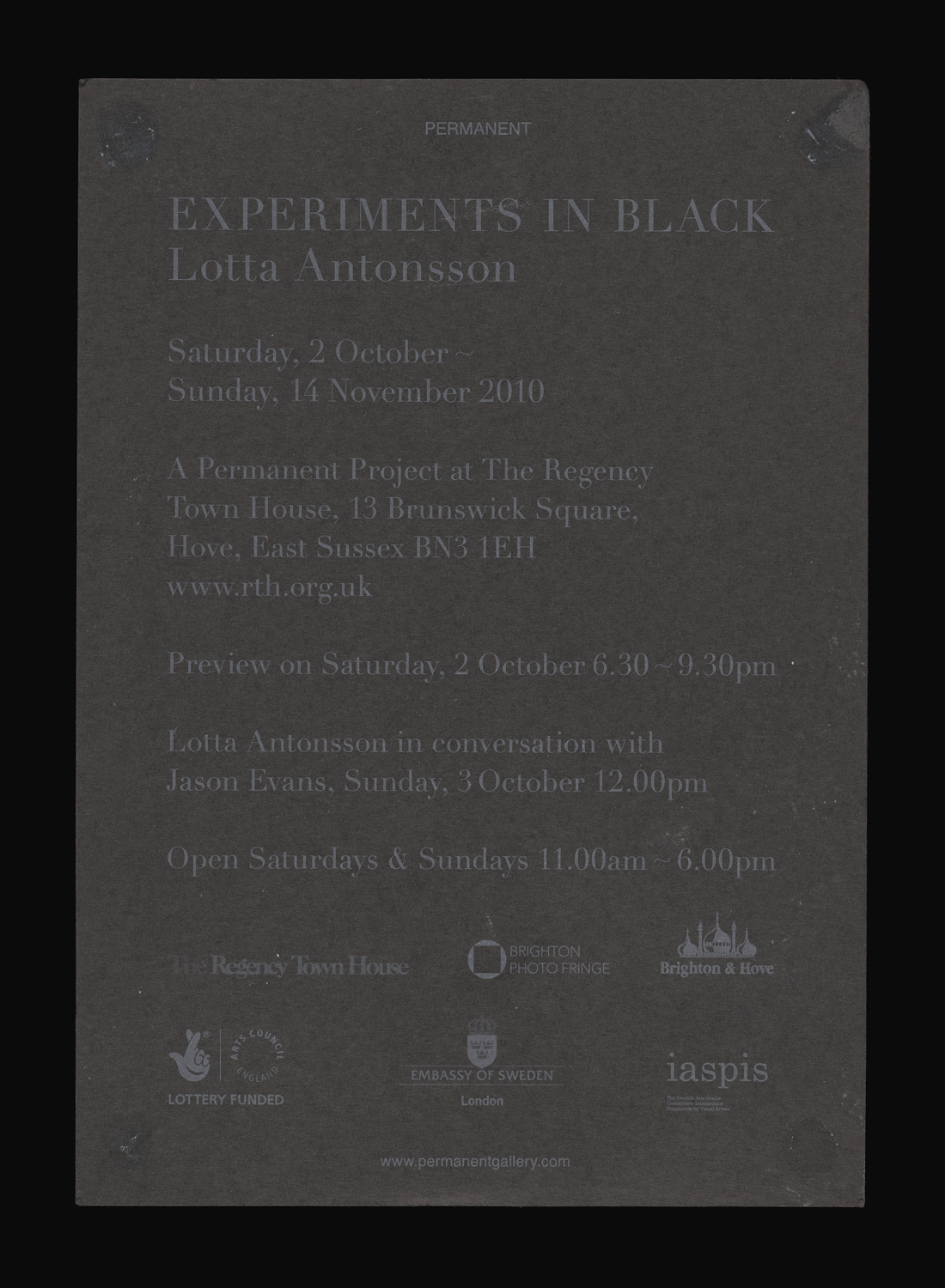

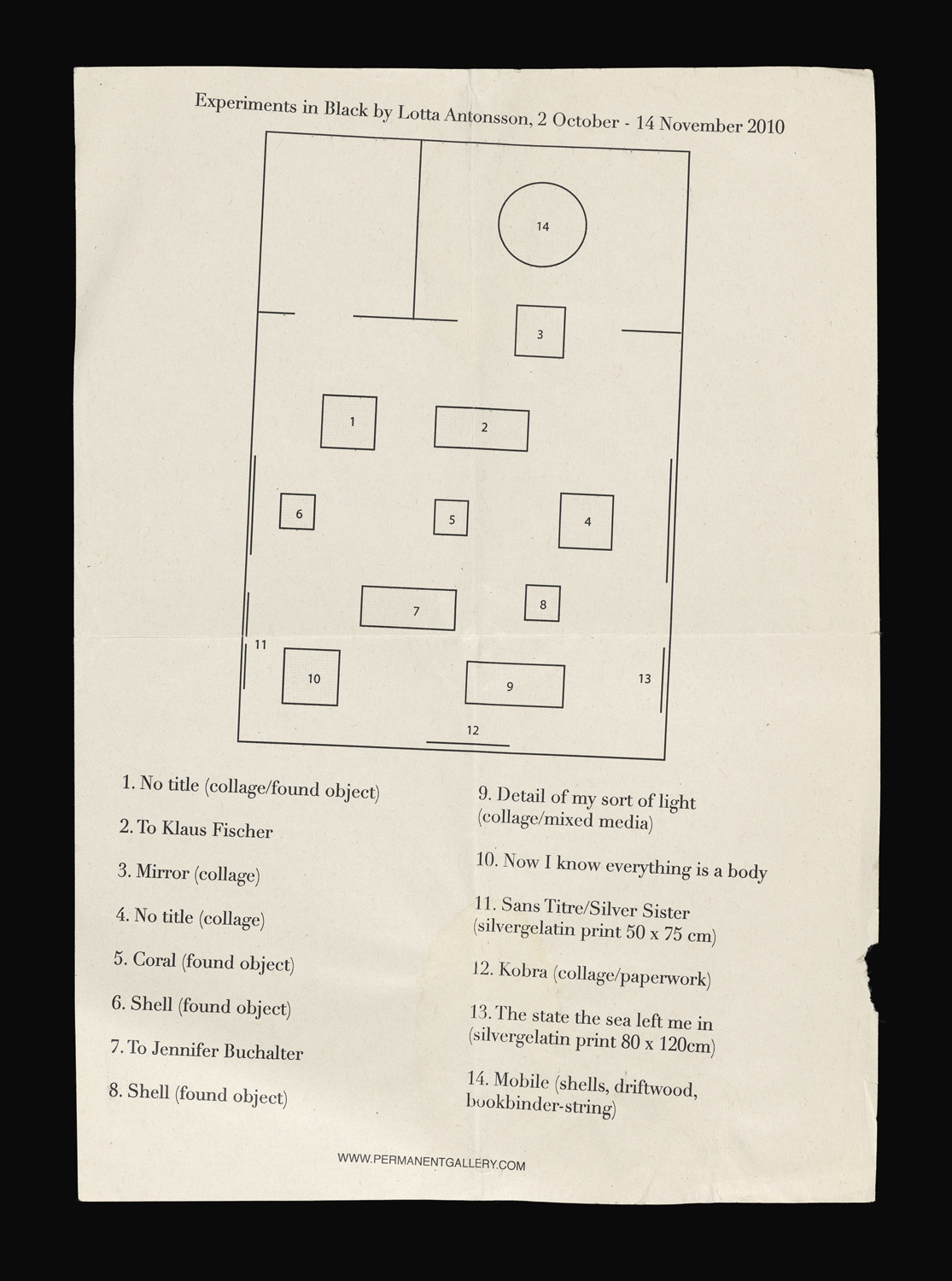

Installation views from the exhibition Lotta Antonsson: Experiments in Black, a Permanent Project at The Regency Town House, Hove, UK, 2010. Photographs: Jason Evans and Lotta Antonsson. Close ups: The state the sea left me in (silvergelatin print 80 x 120 cm) and Shell (found object). Photographs: Jason Evans. To Jennifer Buchalter and To Klaus Fischer. Photographs: Lotta Antonsson. Mobile (shells, driftwood, bookbinder-string) and Double-sided posters (given away for free). Photographs: Jason Evans. Exhibition flyer, 14.8 x 21 cm, Exhibition map, 21 x 29.7 cm and Exhibition text, 21 x 29.7 cm. Reproduction photographs: Andrew Bruce.

Walking from Brighton towards Hove with the sea on our left, we stopped at the bottom of the grand square. Rain-sodden and with the evening already setting in, we crossed the main road and up the hill towards The Regency Town House. Along the row of tall white houses—all of them looking out onto the square and the small gated park. Up a few steps we went, past the wrought iron railings and into the entrance hall of the house; straight up the grand staircase and round to the right—into the front drawing room and Lotta Antonsson’s installation Experiments in Black.

From inside it already seemed dark out. Hanging slackly from the high ceiling a single bare light bulb cast a dim light over this first room. Across from the doorway were three tall windows facing out onto the square. Condensation was streaming down the inside of them in heavy beads. The windows were black. Arranged in dialogue with the sights, sounds and social behaviours of the square outside and the house’s own rituals, the installation Experiments in Black offered a temporarily expanded and pulled apart photographic form, one that questioned the very mechanics of the medium; an experience that was heightened that evening by its isolation inside of a wet inky blackness. Neither I, nor the room, appeared reflected in the wet glass, a phenomenon which drew my gaze back into the room and its contents.

I saw walls stripped of paint and covered in bruises of exposed plaster—it was rough around the edges. Looking upwards I could see the light was suspended beneath a large elaborate plaster ceiling rose. This floating ball of light was reproduced endlessly between two large mirrors that framed the room on opposite sides—one above the fire place to the left, and the other large and looming upwards from the floor on the right. Light spilled both upwards and into the front drawing room from a bright redhead light pointed at the ceiling in the second smaller room. Casting long, warm, beautiful shadows on the ceiling amongst the plaster work, it made you look up. Occasionally the light would be interrupted as limbs of a mobile made of driftwood, shells and bookbinders string, suspended in the doorway between the two rooms, swung past the lamp. This, or when other visitors made their way around the installation and passed the warm light, plunging what you were looking at into fleeting darkness.

Beneath the rose in the front room, ten untreated pine plywood plinths were arranged across the room, almost like furniture. Some topped with mirror in which the light appeared reflected again. All of them varying in heights, shapes and volumes. Some squat, long and low, others tall and thin. Lying, standing and leaning upon these surfaces were a selection of objects. Carefully and purposefully arranged, they faced away from the windows and towards the entrance. Ripples of wood grain warped around the surfaces of these bodies and underneath the puzzled collages and objects meticulously arranged on top. Each element appearing to be chosen or arranged to make use of its very specific physical qualities. Everything appeared tactile and familiar, both highly desirable and photogenic—a heady combination. They were the kind of things you wanted to pick up and take home with you.

Moving around wasn’t easy, you had to navigate and negotiate between each plinth, bringing new combinations and constellations into view in the process. The mirrors on the plinths in the front room not only reflected downwards the scattered matter placed on their surfaces, replicating and reproducing them—it also reflected the ceiling above, bringing the intricate plaster work into play as a live picture. The space between the carefully selected groups of objects, their reproduction and the ceiling above appeared reduced. Suddenly this coral lying on the surface of a mirror was now next to that plaster rose. Or that book or cut-out image of a wooden surface was now lying next to that limb-like plaster cast, which was in turn next to the folds on the ceiling again. My eyes moved from surface to surface to surface. The boundaries between Antonsson’s own images and her use of the images of others was uncertain, as too were those between original objects and photographic or physical representation of them. At the hands of Antonsson this blurring manifest as an oscillation with the occasional flash of familiarity—something that continued as I moved around and among the various plinths, moving and shifting associations freely between everything, all at once.

As I walked around I was suddenly aware of someone beside me reaching out to a book propped open on top of one of the wooden plinths. Picking the book up, they started to thumb through it. For a couple of seconds, I stood there watching, thinking that surely they knew not to touch anything—yet, at the same time, totally enjoying and understanding the feeling of compulsion that they gave into to touch one of these simple things. Like a flash a man swooped towards us. He gently explained that these items were not for touching, and that the artist had left this particular book open to a certain image. The book was put back and carefully rearranged, the man knew which image to turn to. Just like that my curiosity for touching this material had been fulfilled.

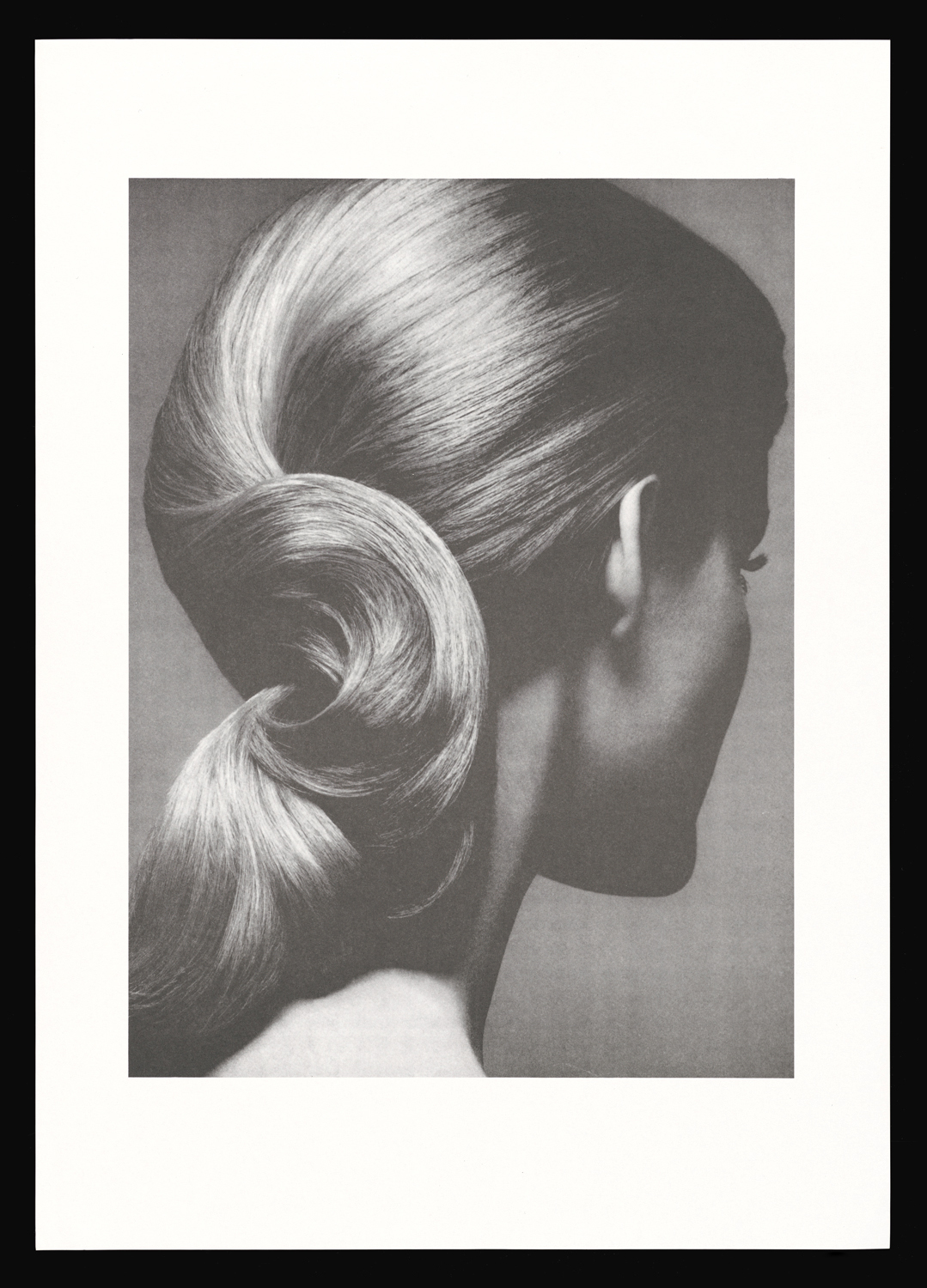

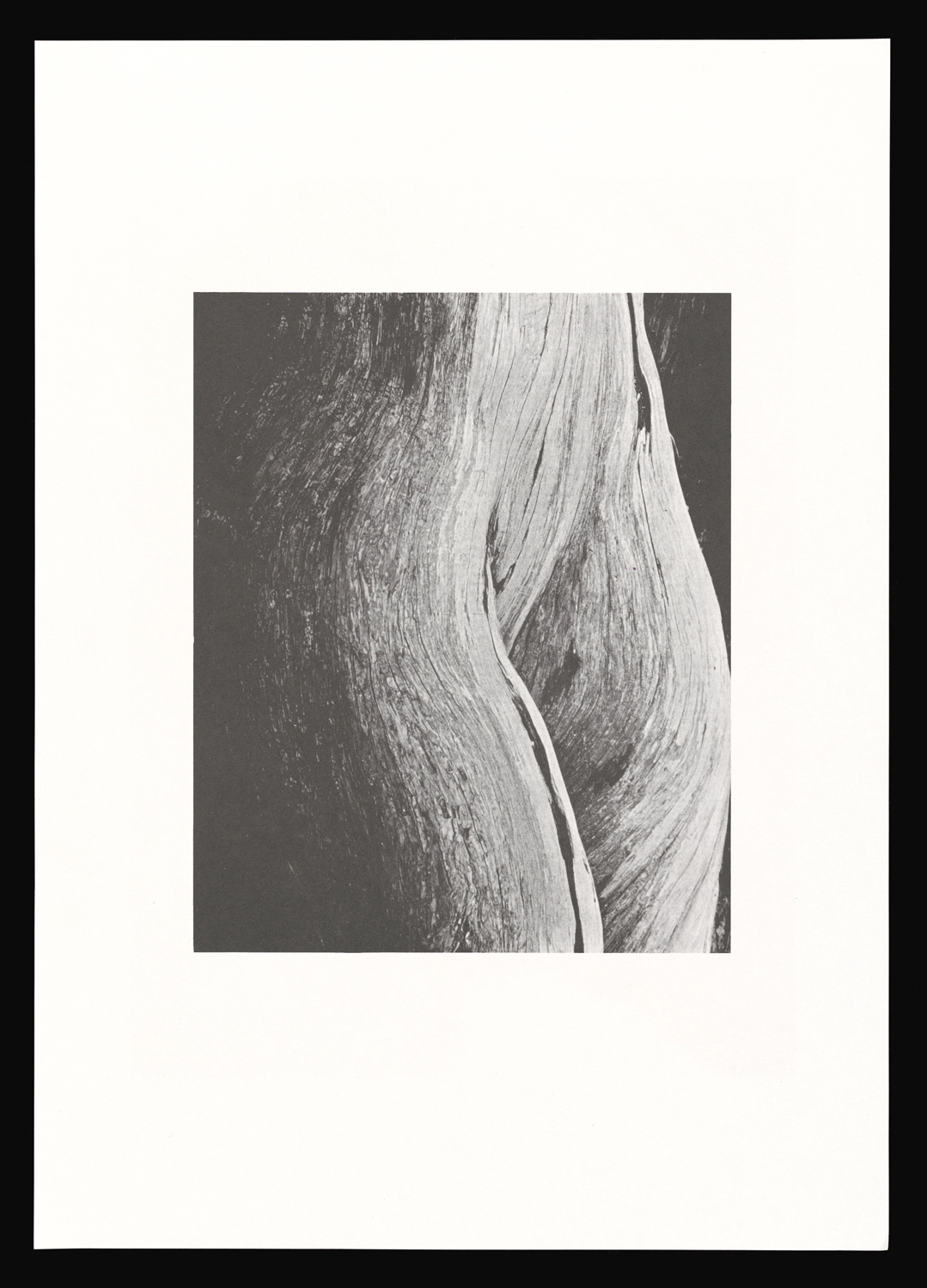

Double-sided poster given away for free at the exhibition Lotta Antonsson: Experiments in Black, a Permanent Project at The Regency Town House, Hove, UK, 2010. Dimensions: 29.7 x 42 cm. Images: Lotta Antonsson, Design: Alex Rich. Reproduction photographs: Andrew Bruce.

Lying in one of the corners of the first room were two piles of posters, free to take home. The stacks each contained the same, double-sided poster—with a different image printed on each side. One pile had one image facing upwards, and the other stack had the other. Neither the same size or format, these two very different images floated within fields of white, inviting a choice: this one, or that one? I took a poster home and a few days later stuck it to my window and took a photograph, forcing the two images into one another.

* * *

Experiments in Black was Lotta Antonsson’s first solo exhibition in the UK. The site-specific installation took place in the drawing rooms of The Regency Townhouse in Hove, an on-going restoration project and museum located on Brunswick Square. Antonsson was invited to exhibit by photographer Jason Evans who also appeared in conversation with her in the space. Part of the 2010 Brighton Photo Fringe, the exhibition was an off-site project for Permanent Gallery—then a gallery space run by Laura Mousavi a few streets away. The Regency Townhouse has been used as a significant venue for the Photo Fringe for many years with each exhibiting artists having to navigate the limitations caused by the on-going restoration work. Nothing can be fixed to the walls which has resulted in many innovative approaches to exhibiting photography within the buildings many rooms and annexes. Other notable exhibiting artists have included Peter Watkins, MacDonaldStrand, Emma Critchley & Nadège Mériau, Martin Seeds and Sam Laughlin.

Experiments in Black was a world away from the 2010 Brighton Photo Biennial, that year curated by photographer Martin Parr. Through Parr’s curation more work was exhibited in the Biennial than ever before (or has been since). This was achieved by digitally outputting all of the work in-house and hanging them up with magnets (including reproductions of original photographs from the Design Council’s Picture Archive housed at the University of Brighton). With exhibition venues across Brighton and Hove, it was marketed as the world’s first ‘frame-free’ Photo Biennial. This approach showed a

lack of sensitivity towards the relationship between what’s in an image and how it is shown. It affectively flattened the hierarchies between exhibiting photographers but also those between individual works, obliterating the nuances of many works. Experiments in Black offered an alternative, slamming on the brakes and claiming photography back, questioning more than what was in front of you—stepping out of the picture to get back to photography.

The gathered photographic material in Experiments in Black makes particular reference to social, political and artistic movements of the 1960s and 70s, as does much of Antonsson’s work. This very particular material and Antonsson’s relationship both to it and of use it is discussed as a kind of “photographic play” by Charlotte Cotton in the essay Arrangement of Ideas[1], which accompanies Antonsson’s 2016 monograph I am a Woman. However, Experiments in Black also significantly extended this through the inclusion a number of Antonsson’s own images—yet, which ones were her own, and which ones were from her collection, wasn’t necessarily clear-cut. That was until you recognised a particular image or book, or when she chose to dedicate a work to a specific photographer through her titles. In Experiments in Black this was Klaus Fischer and Jennifer Buchalter. This uncertain blurring of authorship and ownership arises often in Antonsson’s work, with a pioneering use of appropriated images characterising her output since the early 1990s.

Through Antonsson’s use of installation, assemblage and collage techniques, this specifically analogue photographic material engages with the other types of material that she collects, assimilates and constructs for her work, creating intricate and choreographed systems of association. This material often includes corals, shells, fossils and semi-precious stones. Through her installation and arrangement of these items Antonson, in the words of Patrik Andersson “suspends us in a space that is both personal and political [2]”. Specific to the installation at The Regency Town House were items Antonsson gathered in Brighton, as well as those made in response to architectural features and the restoration work of the building itself. In conversation with photographer Jason Evans she described the installation of the exhibition as being like a one-week residency which allowed her time to respond to, find and make objects for the spaces at The Regency Town House. This was done in collaboration with the Town House’s renovation team led by Nick Tyson and included plaster-casts taken from architectural details of the building as well as a cast of Antonsson own face.

Antonsson’s discoveries about the previous qualities and purposes of the drawing rooms she exhibited in, informed both the physical arrangement of the installation and the materials she chose to work with. Sometimes referred to as the ‘ladies’ rooms’ or ‘chambers’, these rooms were for withdrawal—for reading, looking at pictures through a magic lantern and for playing or listening to the piano. Containing plants, these rooms, with their decorative plaster leaves and roses, looked out onto the square and the gardens in the park, linking the house to the nature outside and beyond. This nature was reflected back into the room again in the exhibition as objects or images that Antonsson brought with her from her own collection, matter that was thoughtfully incorporated into the space together with the plaster casts she made. Driftwood gathered from the beach at the end of the road was also incorporated into the installation, including a large beam from the old West Brighton Pier, used with permission from the local council in the work “What the sea did to me”.

Experiments in Black offered a site-aware response to its surroundings, one which brought together existing elements and components from Antonsson’s practice in a specific constellation in dialogue with its locality. It has had an expanded and continued life with elements first appearing as part of the exhibition Exercise en forme noir at ALP/Peter Bergman in Stockholm in 2008. Since then elements of Antonsson’s installations have continued to return, to be reused and remade within her wider practice—both appearing as her own works and through the sustained use of her collected and manipulated source material. They form component parts of her installations and have been included as both documentation of such and as source material in her first monograph I am a women published by Art & Theory in 2016. Exhibitions in which these elements were either incorporated or from which they were extrapolated include Tre fotografer. Tre tendenser. at Marabou Parken, Stockholm (2012), Photography is Magic as part of the Daegu Biennial of Photography, South Korea (2012) and Det synliga at Artipelag, Stockholm (2014). This reusing, remaking and re-presentation in Antonsson’s work weaves new layers into each presentation of her work.

* * *

Four years after seeing Experiments in Black, I finally saw the small publication that was made to accompany the exhibition. Like the installation itself, the simply stapled black-covered publication brought together Antonsson’s own images, collages and arrangements as well as appropriated images by other photographers from her collection. The publication also included a specially written text by the photographer Jason Evans.

Designed by Alex Rich, who also designed the takeaway posters, the publication was cheaply produced in very limited numbers as four different versions, each with a different series of images. Some images appeared in all four versions, while others were only included in one version—with the series Geometries of Love split across the four different publications. Looking at one of them now, the publication is a little difficult to open due to its binding, you have to physically pull apart and separate the pages to see each roughly printed image fully. The printed images are photocopied versions of original arrangement and collages made by Antonsson in which the blacks are rendered as flat physical fields by the photocopy toner.

Interspaced between the thin white image pages are thicker black pages upon which the text written by Jason Evans appears. Printed in glossy black on black the text winds and shifts between two gendered figures and a child, and between similarity and difference— slipping between in and on the surface of things, to the transformation of them through time, orientation and damage. These shifts, translations, repositionings and juxtapositions are photography theory manifest as fiction—just one that doesn’t assume a singular position. With text you give photography context and meaning, but here this doesn’t mean this, it’s both about our relation with photography and photography’s relation with context. These layer simultaneously and it is something of this that is also met by Antonsson’s use of her source material. Whether it be photography as various forms of printed matter, collected corals, shells and driftwood or plaster cast objects. Antonsson’s work opens this material up to new associations for us through combination, arrangement, transformation or transfiguration. This is further multiplied by the four different versions of the small book for which Evans’ layered text is the only constant.

* * *

Thinking back on my experience of visiting Experiments in Black in 2010, there’s a discrepancy between what I remember experiencing and that which is visible in documentation images of the exhibition. I’ve only seen a few photographs of Experiments in Black taken during the evening, yet those were lit with flash and therefore don’t reflect my particular experience of the show. Other installation photographs I have come across (including those that accompany this text) were taken during the daytime when the two rooms were flooded with light.

It’s these discrepancies, between what I remember and what I see in the installation images, that keeps me coming back to the exhibition itself. That, and the layering of knowledge and associations that Antonsson facilitates in her work—which through our conversations together continue to surprise me. Looking back Experiments in Black isn’t about meaning or whether this means that, to me it’s about the feelings and meanings between things. Feelings or relationships that reveal themselves to you layer by layer over time—the more you put in of yourself, the more you get out.

A few years ago I came across a copy of the book Träd by Swedish writer and poet Arthur Lundkvist, illustrated with photographs by Rolf Blomberg. I was perplexed as to why the book felt so familiar. It took some time, but after a while I realised it was there, hidden in one of the foreign installation shots—a copy of Träd propped open on a stand to pages 92 and 93. I can’t be certain if this was the book that I saw being picked up, but it did open up a whole new wealth of associations—ones that continue to grow the more I think and talk about Experiments in Black.

* * *