“...in the end, the question is not whether

you can get to know the unknown or not, but

rather how you go about searching for it, how

such a trip could be made.“

Free quotation from: Rebecca Solnit,

A Field Guide to Getting Lost.

There’s a small photograph resting on the surface of the moon. It was left there in 1972 by American astronaut Charles Duke during the Apollo 16 mission. The image depicts Duke, his wife and their two sons. Or, more accurately, it might still depict them, a family of four standing on a green lawn, smiling at the camera lens. While the cameras taken to the moon were made to withstand the inhospitable conditions there, the image that Duke left behind was not. What might remain in the harsh UV-rays of the sun is the paper that once held the image, and perhaps the inscription on the back of it. The gesture of bringing a family photo to the moon and leaving it there prompted me to think about family and how photographs have been used to bridge great distances within them.

In the book Man in the Moon, editor and writer Stephanie G’Schwind has gathered essays dealing with fathers and fatherhood. In the introduction she writes:

“It seems for many of us that a father can be at times so unknowable, the distance between him and his children so great, he might as well be the man in the moon.”

Astronaut Charles Duke knew he would come to be a man on the moon, but refused to be the man in the moon to his children. In the months leading up to his departure, Duke invited his family to the NASA training compound where they got to see the lunar module, visit the launchpad and take part in their father’s daily routine. Two years earlier Duke had been part of the back-up team for Apollo 13, a mission that went famously wrong. Three years prior to that, the entire crew of Apollo 1 had perished in a training exercise. Being part of a NASA space program unarguably meant facing the risk of one’s own death.

In the 2014 documentary The Last Man on the Moon, fellow astronaut Eugene Cernan reflects on his life as an astronaut and family man: “I was gone. I was gone, gone, gone. It was a very selfish life. On my part, and on the part of all the guys.” The story of the Apollo space program is undeniably the story of fathers leaving, over and over again, sometimes never to return. The story revolving around Charles Duke and his family photograph alludes to a father trying to understand what his leaving is doing to the children – like he was glimpsing a voyage that they would undergo in his absence, a journey fraught with just as much uncertainty and exploration of dark, uncharted terrains as his own. The reason why Duke asked a friend to take the picture of him and his family was so that he could bring them with him. He used photography as a tool to talk about something ungraspable to a young child - their father leaving, not only their house but the planet. He turned the whole endeavour into something that fitted in the palms of their small hands. A precious object depicting their family huddled together, as to seek comfort and draw strength from each other in this strange, new landscape. Left on the moon, the family confined to the photographic paper, they would look down on earth through space, their likeness slowly fading away. When on the moon, Duke took a picture with his Hasselblad camera of the family photograph that he would leave behind there. In the picture you can see the Duke family on the lunar surface, the barren, grey soil of the moon juxtaposed with the flourishing, green lawn in the photograph. When Duke said that he wanted to take his family to the moon, referring to the photograph that he would take with him, he touched on a historically common notion – that cameras are contraptions for taking a part of the subject’s soul, a concept often attributed to the Native Americans.

In 2008, French artist Sophie Calle was part of the Disko Bay expedition to west Greenland together with 40 other scientists and artists. The work Calle made on site is also rooted in the concept that a portrait could be thought of as something intimately linked to the physicality of the portrayed. In her luggage Calle had a black and white portrait of her mother, who had passed away two years earlier, together with some other of her belongings. Calle’s mother had nurtured a dream of one day visiting the North Pole, a dream that never came to fruition.

Calle writes “I buried the portrait, the necklace, the diamond. Cried a little. Took a photo…Now, my mother has gone to the North Pole.” Just like in the story of Duke and his family portrait, photography plays a dual role in Calle’s trip to Greenland: the photograph as an object, and the act of photographing as a performative act and a ritual. In both instances, they left images on the ground, and proceeded to take pictures of the setup. Calle has written about the journey and the gesture of leaving her mother’s portrait and belongings behind in Greenland. “I wonder if her glacier will advance or retreat, if the climate changes will carry her to the sea to be taken north by the West Greenland current, or retreat up the valley towards the ice cap.” The Independent, a British newspaper, has quoted Duke remembering the phrase he used on his family; Would y'all like to go to the moon with me? The phrase equates bringing the family to the moon, and bringing a photograph of them. Calle uses the pronoun she when referring to her mother’s belongings and the photograph of her, as if some essential part of her mother actually made the trip together with her, and now remains there.

“The far seeps in even to the nearest,” Solnit writes in her book A Field Guide to Getting Lost, pointing to the link between far and near, intimate and alien. In both the case of Calle taking her mother to the North Pole and Duke bringing his family with him to the moon, this correlation exists.

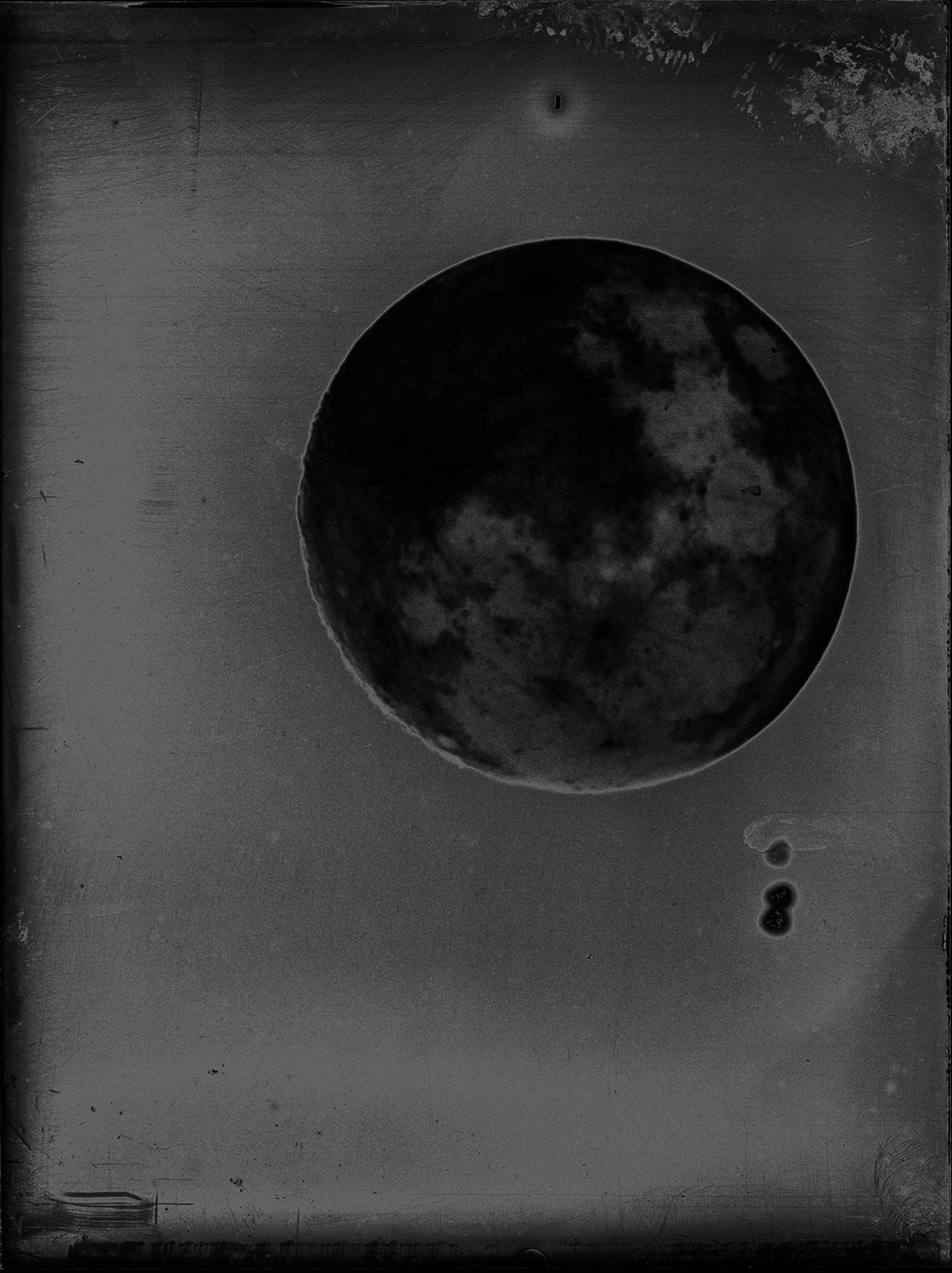

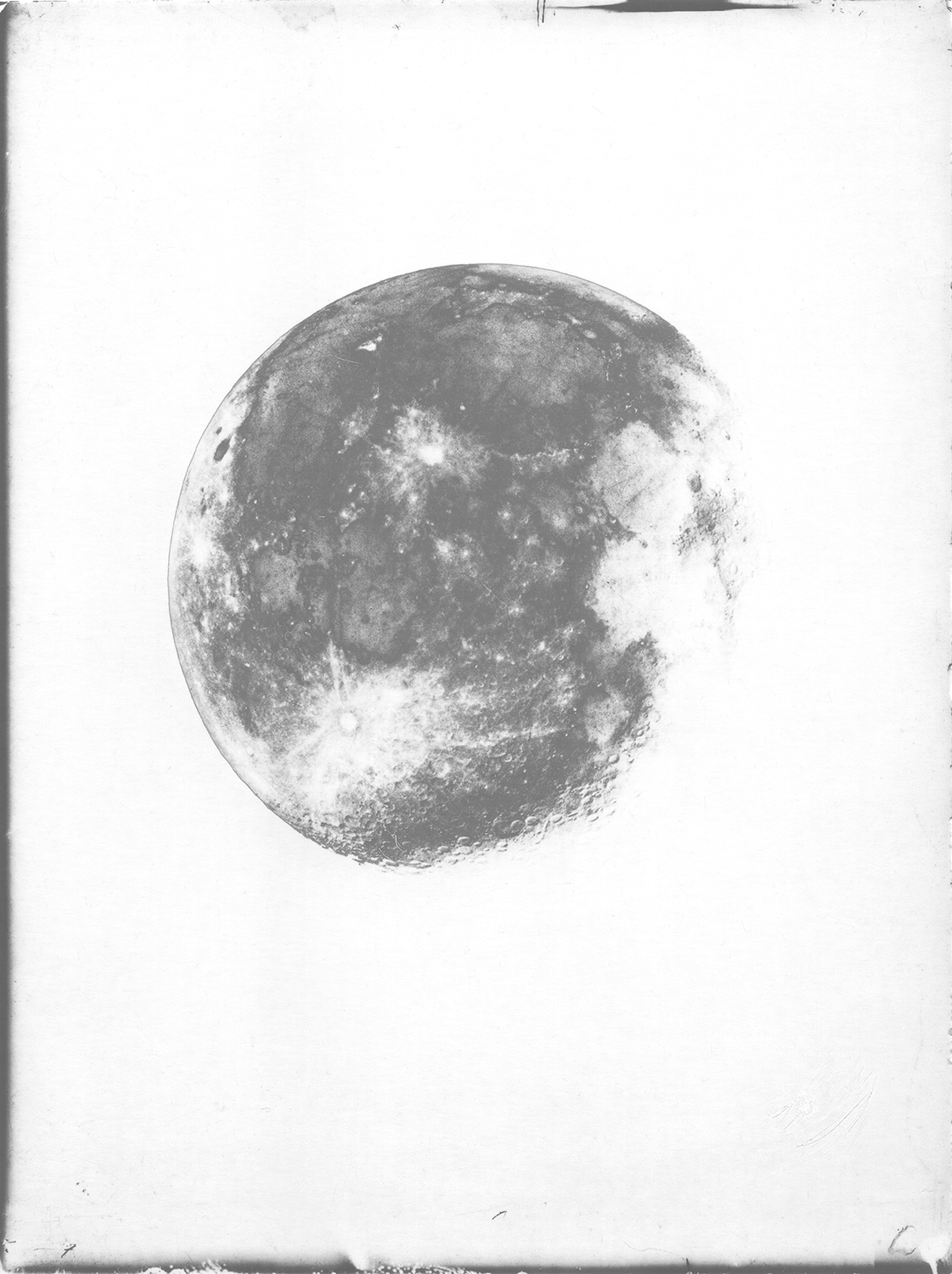

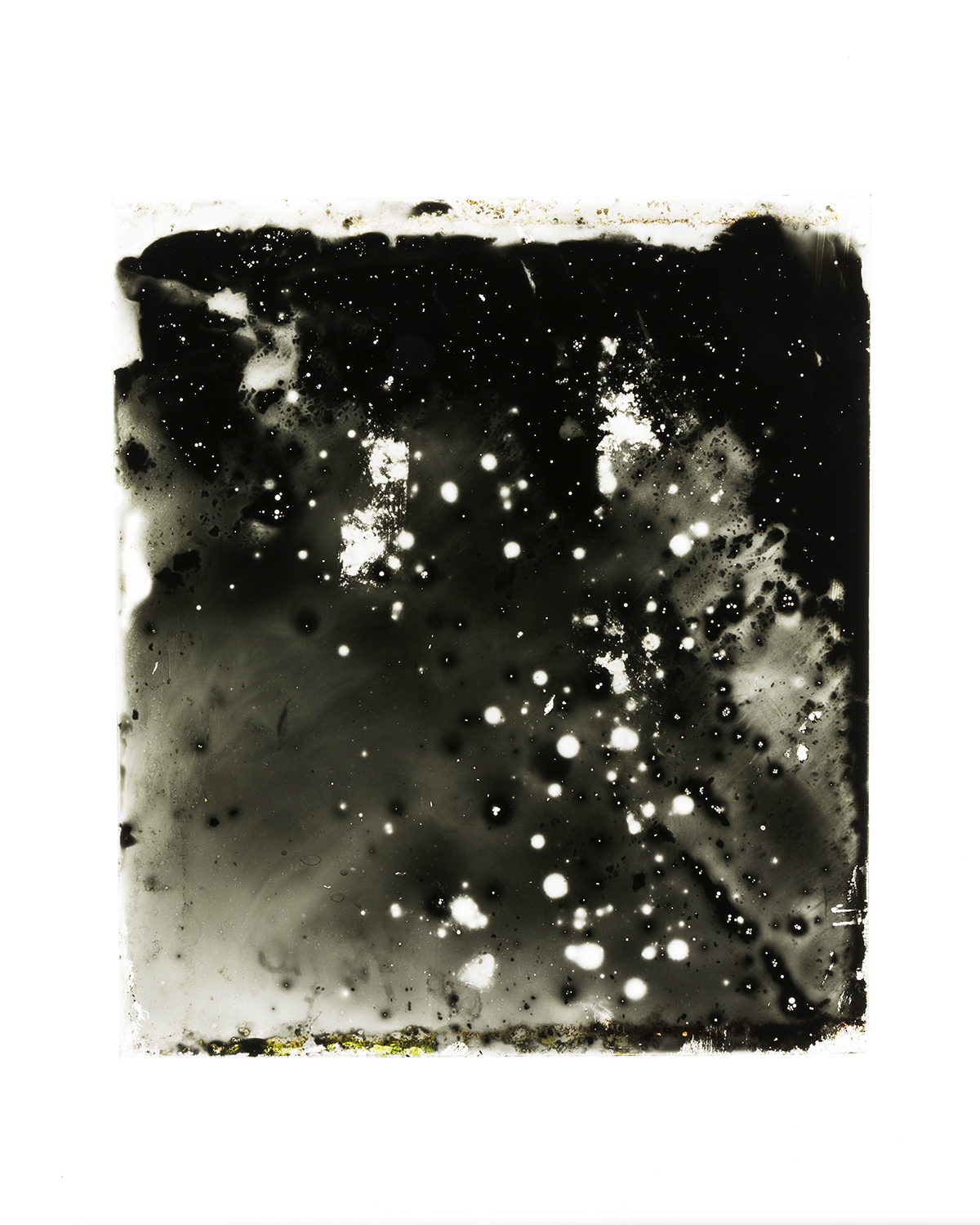

Image Johan Österholm: Polaroid Lunagram (Moonrise), 2014, Contact sheets on polaroidfilm from glass-positives from the 1920-ies exposed by the full moon shine.

In his classic book Ways of Seeing from 1972, John Berger discuss context as a key variable when considering images. The context of the two images that I have talked about are in both cases extreme isolation, one left on the moon, the other on a remote iceberg on the North Pole. These are indeed strange resting places for objects depicting loved family members, but perhaps eloquently illustrate Solnit’s thoughts, that the distant also resides within the intimate.

When I was in my early teens I experienced, as many do, inner turmoil at the prospect of leaving childhood and entering in to a new realm, one of responsibility and gravity. My dad was working away most of the time, and I often found myself kneeling on the floor in front of a small, wooden table. On the table I would place a framed black and white portrait of my father as I proceeded to call him on the phone. As I talked to him, his voice soothing me, I would rest my eyes on the image of his smiling face.

There is more than one way be distant as a parent, but only one way to be truly present. In lieu of that, we have the telephone, we have the photograph. Photography can create the illusion of presence, stir up longing, distort one’s memories, but it also has the ability to comfort.

Using photography, Duke tried to accomplish the impossible – to keep his family together, or at least give shape to the illusion of control. The act of photographing must have played an important part when preparing the family for what was to come. The ritual of gathering the family in front of the lens, and then to introduce the idea that the whole family was coming with him to the moon, using the photograph as an extension of his thinking. Not only was Duke exploring the dark, vast space when going to the moon, in a way he was also exploring fatherhood in a time of social turmoil and changing family dynamics in America.

It seems some of photography’s most elusive qualities are to be found in the story of the Duke family photograph on the moon. There is really no way of knowing for sure whether the image on the moon has faded from the sun’s UV-rays, no telescope can focus in on an object that small and far away. Therefore, the story and the gesture are just as important as the image itself. Photographs as objects have been used as a way for us to take complex thoughts and feeling and transform them into something that we can touch, something that we can place in front of us. Like totems, photographs have been used in these ceremonial efforts to bring what is distant closer. When so many of the images that we see today remain in the digital sphere, never to enter in to our physical space, has the way that we interact with and think about photographs changed? I’m not sure I would have been as intrigued had Calle or Duke left memory sticks containing images of their loved ones behind.